George Gendron is a flying car

Flight: A series of conversations Flying Car is having with individuals that are contributing, surprising, and delighting the world with something new.

G

eorge Gendron doesn’t follow the crowd. Instead, he spots the potential of a crowd to form. Then as an editor and journalist he delivers media to these growing collectives of people, providing content that is useful, relevant, and inspiring. For over three decades, Gendron has offered stories that help patches of like-minded individuals to coalesce into an empowered tribe. Gendron’s tribes are rooted in the creation, growth, and sustenance of business-oriented communities that share an identity and a vision.

Go back to the early 1980s when the idea of “entrepreneur” lacked the cache it does today. During years when “startup” wasn’t yet a word, Gendron helped transform the concept into a movement. As editor-in-chief of Inc. Magazine, he stewarded it from from a magazine covering an obscure part of the American economy into the premier publication for growing small businesses around the world. Creating the Inc. 500 (now the Inc 5000), he turned it into an institution, this annual list of entrepreneurial success stories serving notice to corporate America that there were baby tigers in their midst. Many companies first introduced in their infancy on Gendron’s list later grew into global brands. Think Microsoft. Think Charles Schwab. Think Apple.

Whether from restlessness or perpetual curiosity, Gendron did not stop there. After selling Inc. Magazine to Betelsmann Media, Gendron founded Clark University’s Innovation and Entrepreneurship Center, the country’s first such program for under-graduates. He also started several non-profits, including AllWorld, a global organization that grew from a project he founded in 1997 with Harvard Business School professor and business strategist, Michael Porter, profiling successful entrepreneurs in under-served markets.

Today Gendron is a year into his next venture serving an emerging business tribe. His newest media focus is with a team creating content for the community he calls “soloists,” the freelancers and independents who together are unacknowledged as among the most important growth segments of the American economy. Gendron isn’t just adding gravitas to the term “freelancer” by rebranding them as “soloists.” He and his partners are actually supporting a deceptively powerful part of this nation’s business infrastructure, a group of independent professionals who – with media like he and his partners can provide – can coalesce into a genuine force.

What most excites you about this population when it comes to business and work?

For a lot of people – including myself and my partners – there’s a fascination with what we call small-scale capitalism. Where the consequences of your decisions are very real. There’s nothing abstract about your decisions. The second thing is we feel that increasingly with the tools that are available to us, you’re able to work with partners you respect and where you work. And it allows you to choose to work on the type of work that matters to you. Work that you think is important and is worth doing really well. I’m not arguing that the solo life is idyllic but I’m saying that you have more control over who you work with, where you work, and what kind of work you’re doing or reject.

From my own experience, it can also bring a lot of anxiety, of constantly wondering, “Where’s my next project.”

We did an event with 150 soloists, and asked them that question – “what’s the biggest source of anxiety?” They said, “work flow.” Which meant they either had too much work or not enough. That doesn’t go away.

But if you want to talk real anxiety, talk to people who are working at troubled companies. Talk to people who have just survived the latest round of downsizing. It’s brutal out there. The percentage of Americans who feel they have good jobs, I think it’s 14 percent. So you do trade off one set of anxieties for another.

What should the businesses that retain soloists keep in perspective in using them?

There’s a firm I know who consider their freelancers as among their best employees. I mentioned this to a group of business people and they asked, “what is their pay policy with freelancers?” This firm pays upon completion of the work. Immediately. This group was astonished. It’s not “net 90 days.” All to say, paying quickly is important.

The other thing soloists want are clarity and transparency. They want honest feedback on their contribution. They want to feel that their work is respected. When I say “transparency,” they want a solid evaluation of their work. They want to know that they’re hitting the mark.

What do soloists need to consider when working with growing businesses, especially startups?

It’s easy to be taken advantage of as a soloist. And as the population of soloists grows, it will be easier for businesses to shop around. If you’re a designer, instead of someone paying you the hourly wage that a really good designer warrants, a company might figure they’ll go on freelancer.com and get a logo for $25. So freelancers can develop an attitude of being taken advantage of.

That can backfire if soloist forget that they’re dealing with startups. When startups are starting, they’re boot strapping. They have very limited access to resources. The thing about startups is all the traditional rules of business are suspended. It really is pure survival. So we really have to count on the trustworthiness of the people both in the startup and the people who surround it offering the work.

It sounds like there’s a need to create new arrangements that work for both the business and the soloists.

Absolutely.

You’ve started several successful businesses and organizations. What’s the challenge and opportunity of starting a business or organization today?

This is an amazing time for people wanting to go out on their own to build organizations of all types. The reason it’s particularly good right now is because of the tools. The access that individuals and startups have to technology and software and apps. The type of infrastructure you can build for yourself wasn’t possible just a few years ago.

What hasn’t materialized yet in the startup and small business space is big data analytics. It’s interesting because technological advancement initially benefits small companies. It levels the playing field. Big data not so much. It’s being capitalized now by big organizations and only recently starting to percolate down into the ranks into middle market companies. It’s expensive. The talent has been bid up. It’s hard to find competent people. But in general the tools make it an unbelievable time for small businesses and startups to box above their weight, so to speak.

A disadvantage that young entrepreneurs experience is living in a period where so much emphasis is placed on unicorns; billion dollar companies, instant valuations – all venture backed. That creates the illusion that is the world of startups. It’s not.

Technology is only six-to-seven percent of our GDP. So there’s lot of people launching more mundane companies. Companies where the challenge and opportunities are really the same that they always were. With the one caveat that, in some sense, every company has to be a “technology company.” Not just a tool that let us manage effectively but tools that provide more value for consumers.

What is the importance of story-telling to building a business? As a story teller, yourself, and someone who has grown businesses and understands business, what do businesses need to know about “story telling?”

Increasingly these days, consumers want to know a lot more about who is making what they buy. That’s where story telling is an incredibly powerful way to forge a connection between a business and an audience. Telling who are you. Why you’re making what you’re making. It’s like meeting your future mother-in-law for the first time and she asks, “buster, what are your intentions?” Consumers want to know your intentions. Story telling is a powerful way of starting a conversation with your consumers

How about for B2B businesses?

Story telling is a very important tool as a talent attractor. These days it’s an incredibly important thing to attract the right type of talent. By the right kind I mean not just having the technical skills or the domain expertise, but the caliber of people that you want to build an organization that is based on trust. An organization that you can’t wait to get into in the morning rather than one where – unfortunately a lot of young kids are doing in Silicon Valley – to build it and flip it.

There’s something else about story telling. One of the wisest things I was ever told by a board member; he said “you want to get people rooting for you.” You want people to be on your side. “It will work to your advantage in unimaginable ways,” he said to me.

It really is difficult to build most companies. It’s really difficult to sustain positive cash flow. You want people on your side, not just doing business with you. You want them rooting for you. You want them thinking, “I want them to succeed.”

My wife will often say “you look like you’re actually pleased to hand over the money to Jet Blue.” On some level I share a crucial part of their DNA – to treat passengers with respect and have a good time. This is all story telling. And I think it is as powerful in the B2B arena as B2C. It doesn’t always appear as overtly in your marketing brochures. Maybe it should.

We talked about the importance of community for soloists. I wonder whether there’s anything B2B organizations need to consider about building community?

Back at Inc. Magazine we learned a valuable lesson that’s relevant to this. Given the choice to write about a company making widgets or fasteners versus a company making ice cream, you’re going to gravitate towards the company making ice cream. But you quickly learn it’s not what a company makes but how they make what they make.

So many of the companies that we at Inc. Magazine built deep relationships with were companies people never heard of. They weren’t making amazing products but you went into the company and you were dazzled by how they did what they did.

The most fascinating company that I have ever seen in my life is located in Springfield, Missouri. They remanufactured truck engines. Glamorous? Well, you’d go in there and in a half hour you’d feel like “I’m in the middle of the most sophisticated business school.” All of their workers understand the economics of what they do and how they contribute to the company. It was spellbinding. Talk about a sense of community. Everyone was a shareholder. They felt this bond.

Is there a way for soloists to feel part of a community working with a B2B company?

I think of the firm I mentioned previously, They have 25 employees but they have higher billings than a company with only 25 employees. I was interviewing the CEO, and he told me that 40-percent of their billings came from that network. That’s huge; 40-percent of their work is coming from independents. People not on their payroll. The soloist sees a project that requires a larger firm, so they bring in the agency who uses them regularly. In return, the soloist expects a role. What if you built your soloist network thinking as much about them in relation to your biz dev opportunities as their professional abilities? It’s changes how you think about the value of your soloists.

When you think of startups and growing a small business, what is the importance of branding these days?

We can just go back to the classic definition of influencing behavior in at least one of two ways; people will either pay more for whatever your offering or will buy it with more frequency. But it’s a great question because the term “brand” is so overused.

I think 90 percent of the organizations that we think of as having brands don’t. They have markets. They don’t have brands. They don’t have reputations so developed that it influences customer behavior at all. At Inc. Magazine every year we would sit around as a crew to look at the Inc. 500 and say “what percentage of the most successful companies in the US have actual brands?” Very few of them did.

So that suggests that you can build a company without a brand?

Yes, absolutely.

So if they’re successful why would they want brands? What does having “brand” add to the equation?

All the activity that goes into brand building has to be an investment. It should contribute to the economic growth of a company. But it also should contribute to the sustainability of the business. There’s a big difference between having a public image and having a genuine brand.

You meet with startup people and one of the first things they’ll talk about is their brand. And they haven’t even launched yet. It’s one thing to talk about as something you built. You have to build it from day one. That’s one thing. It’s another thing to talk about it as if it exists out there. It’s become a very sloppy part of our language.

And the thing that we’re really missing in the entrepreneurial space is brand auditing. No company in their right mind would finish a fiscal year – at least when you’re established – and not have an audit. You should have an audit where here’s what you and your management think of your company and here’s what your consumers think in an unbiased way.

What have you learned to look for in the groups you work with on branding? The agencies?

Someone who I am absolutely convinced cares about the outcomes of their work. And they care about my company. And they’re knowledgable. I want to believe I’m going to get customized work. There is no work that’s more customized than branding. I don’t want a bag of tricks.

The first thing I want is someone who seems genuinely curious and ultimately passionate – a fan in the best sense of the word – of what I’m doing.

The other thing when it comes to branding work, I look to be surprised. I look for uncommon solutions. So much of the stuff is boiler plate. In an ideal world, branding is thought leadership. It represents your company at its best.

I don’t want to name it, but a very large company sent us 50 pages of marketing materials about their brand. Reading it, I thought, “this is branding?” It was so uninspiring. No surprises. Nothing where it makes you think, “isn’t that a brilliant way to think about their customers?” I didn’t expect to be dazzled by everything, but there wasn’t a single surprise on a single page of this 50-page document.

That surprise and imagination is very important for young companies. Bootstrapping is not just about lacking cash. The other half is using imagination and resourcefulness to get things done. And what thrills me about small-scale capitalism is this need and opportunity is to constantly replace capital – financial capital with human capital. That’s what I look for from my branding firm.

Any examples of that from your work life?

I remember work from a non-profit capacity [where h was a member of the board]. The agency came in and they were showing a first round of work [to the board]. The other five [board members] were legendary characters in big business. I remember a hush overcoming the conversation. This branding group had found a way at looking at what the non-profit did in ways we never had thought of. Around half of it was off the mark but the rest was brilliant.

Those moments are so memorable because there are so few of them. It’s not just creativity. It’s a combination of creativity and resourcefulness and lot of hard work. Really drilling down and understanding the work of the non-profit. The service work. The work in the field. The recipients. It permanently changed what [the non-profit] did.

It reminds me that the most powerful feedback I could ever get when running my magazine was when a CEO called me and said, “I read your story and learned about my company from reading your story.” This is what a branding firm can do. They can see you in ways that you don’t see yourself.

The other thing that I think of branding – which is insidious these days – everyone thinks they can do it themselves. “We don’t need a branding agency. We don’t need PR.” Martha Stewart once gave a speech to a group of magazine editors where she said “I never met a group of people who advertise less than media people.” It’s true. We don’t even believe in advertising for ourselves but that’s what we’re selling. Branding is important.

But it’s hard. Doing a startup always requires managing two opposing behaviors. One is patience and one is urgency. You have to be unbelievably urgent and unbelievably patient. I once was talking to Steve Jobs and I remember him saying, “it’s the hardest thing to do.” They are in conflict with each other.

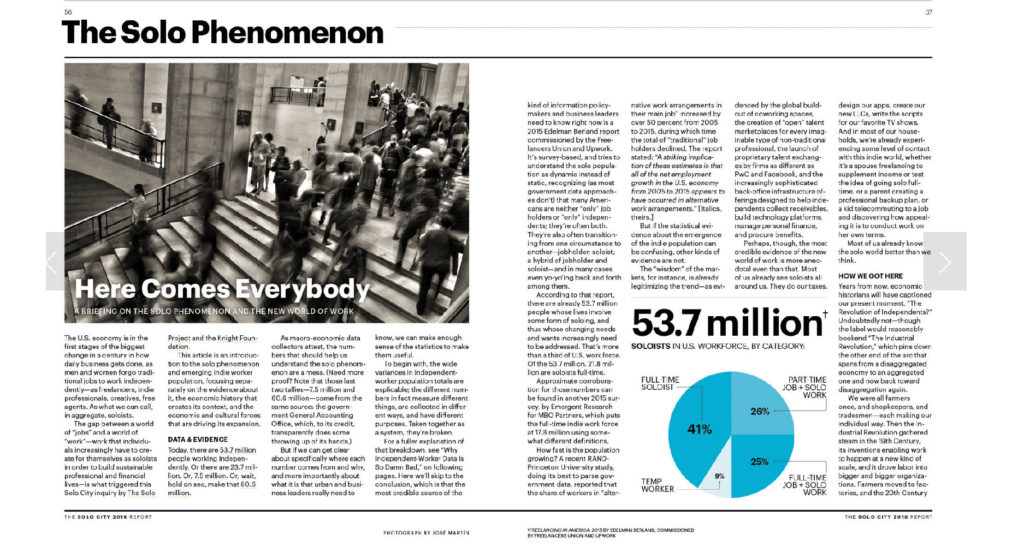

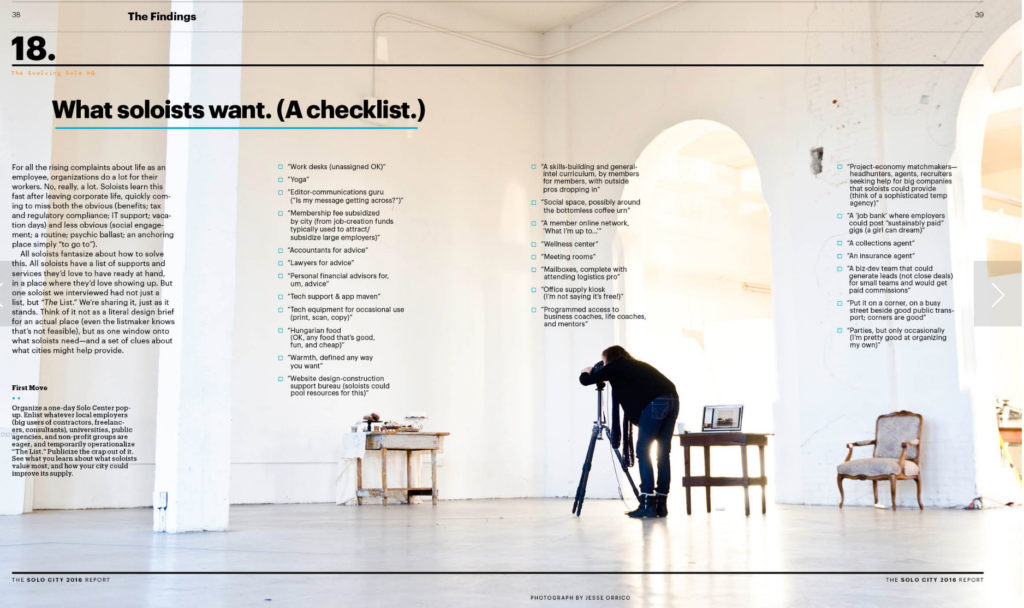

I’m curious about the report you generated about Soloists in America. It seemed geared more toward cities and government rather than business. Is there as big a role for business as for government in meeting the needs of soloists?

It’s a good question. Are there economic incentives this time around for companies to build out an infrastructure or will government play a bigger role? I think business can have a big role. But there are a bunch of people in that report who[m] I respect who say this time it will have to be government. Though they admit that there are very few people who encourage government to do it because the beneficiaries (soloists) are not a powerful constituency.

You think of how traditional economic development has worked. First it was about big Fortune 500 companies. Then it was about entrepreneurship. Now the most dynamic sector so far as job creation is neither of those. But it’s hard getting attention.

Universities have overbuilt their education infrastructure because they go to all their billionaire alums and what do they want to do but subsidize entrepreneurship education. But look back and at one time there was no infrastructure for entrepreneurship. None. In 1980, there were two classes in the US – not schools, only classes in entrepreneurship – both at Harvard. When you look at the infrastructure that’s been built out since then, it’s astonishing. There’s a big incentive for the private sector to build out infrastructure for entrepreneurs. Less so for soloists.

But what we learned at Inc. Magazine was that in any given year, 80 percent of companies on the Inc. 500 were founded by people who had spent at least one year, many for two years, working out of their bedrooms. At the time they were soloists. People would tell me, “yeah, but they knew they would be growth companies.” Guess what… they didn’t!

Eighty percent of the Inc. 500 when they asked at what point did they realize they were building a growth company, they answered “I knew when you called me and said I was on the Inc. 500.” So we asked, “what was your original ambition?” And the typical answer was, “I quit on a Friday and all I wanted was to make as much money as I was making before.” The person then discovers “what I’m doing now, there’s a demand out there.”

Thinking about what all you said, it seems to me that Solo is as much about an ethos or mindset as about a segment. It may not be simply about working solo or staying small as much as about the sense of wanting to work with people you respect and on things you respect. That you don’t have to be a card-carrying member of the soloists to share that sense of solo.

It’s a great point. It’s not about being the “coolest guys on the block.” It’s about a state of mind. It’s that feeling about intentional work design.

George Gendron is a founding partner at The Solo Project, LLC